Clinical Reasoning and the development of a 'working hypothesis' in an elite cyclist

by Martin Krause (2010)

Treatment: Left and right ischiococcygeus release; MET right adductor; in prone with one foam role under right hip and another under the left ASIS I used joint mobilistions, STM and dry needling to the right erector spinae group from T12 - L3. Exercises included Prone Spinal Extension (McKenzie), self release of ischiococcygeus, deep abdominal and iliacus stabilisation exercises during knee drop outs in supine, unilateral pelvic rotations/gluteus activation in supine, cross country skiing exercise with blue theratubing

see link to evidence for dry needling

17/03/2010 (4 weeks since accident)

Less painful walking on stairs

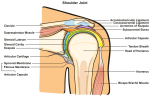

MRI findings : non-displaced fractures of the acetabulum

Very little lumbar IVM during lateral flexion, flexion and extension.

Treatment : STM right anteriomedial hip

Joint mobilisations to right T12-L3

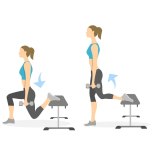

Exercise : Sideways stepping (later off a small step), Prone - gluteal activation during initiation of ALE (active leg extension), Swiss Ball - supine bridging for gluteal activation, 'around the world' in side lying using low threshold activation to rotate the ball whilst keeping the pelvis steady; 4 Point Kneeling - abduction and abd/ext rot, lying prone on foam blocks for pelvic alignment (right anterior hip and left anterior pelvis).

24/03/10

No pain on stairs. New seat on bike making him less stable.

Left Concave scoliosis present on forward flexion, poor IVM lumbar spine. Excessive activity in all superficial trunk muscles and hip muscles. More marked left concave scoliosis on the bike. Excessive pelvic rocking to the right in the horizontal plane, whilst dropping the left hip in the saggital plane. Corrected through transverse pressure through the R6-8 rib rings whilst lifting the posterior right R9-12 rib rings.

Treatment : commenced MET's for upper lumbar/low thoracic right rotation; left rib ring lifts R7-8. Right iliopsoas releases.

MET left hamie for correction of left anterior ilial rotation

Exercises : Pilates Reformer - hip abd, ext in standing, superman with lateral and inferior diaphragmatic breathing

Transverse Adbdo - deep Multifidus training using 'guy wire through body suspending the spine' analogy.

Active Leg Extension (ALE) using 'guy wire stabilisation', descending diaphragm and 'Relaxation with Awareness' technique on the low-mid thoracic and upper lumbar spine erector spinae muscles. Stretching thoracic spine with stretches of the hip flexors, hamies and calf muscles

Further treatments on 30/3/10 , 7/4/10 and 14/5/10 as above, however now with even more thoracic emphasis, plus a big emphasis on detraining the superficial muscles, activation of the pelvic floor - diaphragm as well as gaining 'timing' w.r.t lumbopelvic rhythm in the frontal and horizontal planes.

Client becoming rather anxious to get back on the bike. Wife not too happy to have a moody husband 'hanging about the house' Hence gradual recommencement of cycling during this period

26/7/10

.

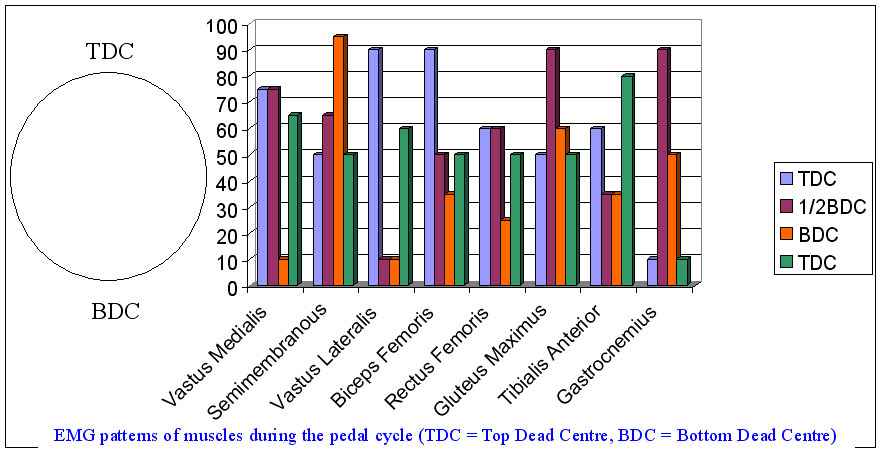

Jay returned 2 1/2 months after the last treatment stating that he had been suffering severe knee pain for the past 2 weeks. It had been of an insidious onset. However he had had a bike fit some 6 weeks prior to the onset of knee pain. At the time he had experienced some mild burning pain in the left ribcage after the new set up. He described 3 distinct pains in the leg - one sharp, the other a dull ache, whilst another sensation was that ' of the whole leg feeling dead'. Dull ache at night. Pain in mid popliteal region during push-off phase of walking. Pain in both the posterior knee and posteromedial knee during the upward cycle through Top Dead Centre (TDC) to 1/2 Bottom Dead Centre (BDC).

.

.

Extension in lying (modified push up, McKenzie technique) was reduced to 1/4 in the L/S

All hip ROM were once again restricted. The One Leg Standing (OLS) demonstrated an Intrapelvic Torsion (ITP) right, with reduced form closure over the left SIJ.

Importantly, the ITP right was accompanied by horizontal pelvic rotation right (contrary to normal clinical prediction) and the left concave scoliosis is on the side with the longer leg!!

SLR with DF was approx 45 degrees and without DF approx 60 degrees on the left and 60 and 70 degrees on the right resp.

Active SLR +ve : better with left R6-9 ring lifts and/or right anterior rib posterior translation

Hip flexion in sitting : In sitting he was unable to lift either leg beyond 90 degrees hip flexion. Lifting on the left resulted in left pelvic shift, on right resulted in right pelvic rotation, these were accentuated on the bike and were acompanied by a left concave scoliosis in the L/S.

The sacrum was vertical and the low lumbar spine was nearly vertical, with severe wedging into flexion occuring at L2/3 and L3/4 whilst seated on the bike.

Localised tenderness and swelling was present in the popliteus muscle. The semimembranosus, semitendinosis, gracilis and tibial nerve were all tender to palpation.

Active Leg Extension (ALE): severly reversed Glut : Hamie timing. Extremely hamstring dominant with associated excessive tension in the erector spinae of the low thoracic and high lumbar spine.

Considerations:

Typical EMG patterns : note the need for Gluteus Maximus activity during the downward pushing phase of cycling. My thoughts were that lack of early Gluteus Max timing and constant use of Hamstrings were overloading the structures around the knee. Additionally, the semimembranosus and semitendonosis internal rotation vector at the tibia being a counter to the adductor vector of hip internal rotation. Moreover, these were preceded by counter-nutation at the left SIJ. Anterior rotation of the ilia makes it particularly difficult to activate the gluteus maximus. Moreover, anterior rotation of the left ilium would create tension in the ilio-lumbar ligament normally resulting in right rotation of L4, where this was accompanied by a significant counter posture of left concave scoliosis in the upper lumbar spine and low thoracic. The wedging at L2-4 may also have been placing Adverse Neural Dynamics on the obturator nerve.

Link to ALE and ASLR and diaphragm

A program to regain pelvic symmetry and thoracic mobility was instigated using a comibination of joint mobilisations, MET's, dry needling, soft tissue massage, and rib ring lifts. Additionally, Adverse Neural Dynamics signs were treated using techniques to the thoracic spine.

Link to motor control and breathing reference

Scapulo-lumbar stabilisation exercises were also given by using theraband whilst using the bike on the 'home trainer' . Hereby, activation of latissimus dorsi and low fibres of trapezius was instigated which resulted in reduced horizontal rotation of the pelvis during pedaling.

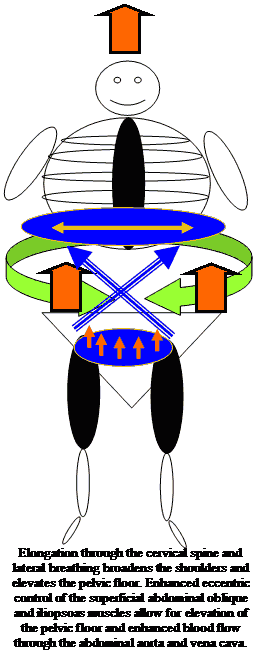

Alexander Technique for Lumbopelvic, Thoracolumbar and Scapulothoracic support through elongation of the Upper Cervical Spine

References

This author used 3 sessions of treatment to the T10/11, T11/12, T12/L1 and L5/S1 to improve the ROM and ability to squat in a patient with anterior knee pain.Grindstaff TL et al (2009) Effects of lumbopelvic joint manipulation on quadriceps activation and strength in healthy individuals. Manual Therapy, 14, 415-420.

These investigators found a significant increase in the ability to produce quadriceps force (+3%) and activation (+5%) immediatley following lumbopelvic joint manipulation

Figure 1: A model of everything : the neuromatrix is used as a model (cognitive process oriented structure) to describe the various input which the therapist can offer to 'enable' the client to engage in their path to recovery. Hereby, an evidence based approach using 'the values and beliefs' of the client is integrated with the scientific evidence base from physiotherapy, the pain sciences and psychology. Importantly, the therapist gains confidence through their success at predictive reasoning, whilst the client gains emotional confidence in their ability to undertake goal-oriented activities without the fear of exacerbation or under-performance.

Heuristics versus Constructivism

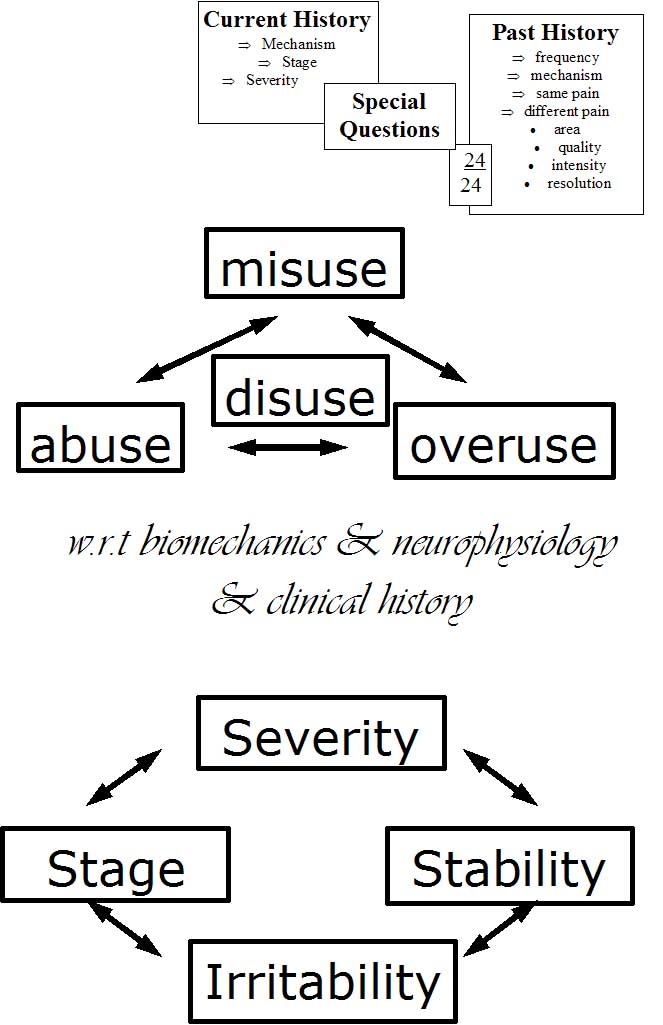

Figure 2: A useful instructional model used to describe a 'top-down' clinical approach with a scientific clinical evidence based approach of biomechanics and neurophysiology.

Figure 3: Increasing the validity and reliability of the clinical reasoning by correlating all aspects of the subjective and physical examination into a meaningful clinical picture (pattern recognition) - adapted from Maitland (1986, 1991).

Treatment as a product of a systematic assessment

Although an at 'out of fashion' terminology, the aggravating/easing factors are a disability measure which can be used to assess the neurophysiological and biomechanical state of the pathology. By analyzing the movement and loading characteristics of the aggravating and easing factors the therapist should gain a measurable outcome tool for assessing the efficacy of treatment. Additionally, the information can be used to correlate it with impairment measures of the physical examination. Improving the internal reliability by correlating information across the entire examination process enhances the validity of your treatment and re-examination process. Ideally, the therapist should have at least 3 aggravating/easing factors to assess outcome. Otherwise, a more in depth analysis of the aggravating/easing factors should be undertaken using inductive reasoning. For example, if the client only complains of shoulder pain when lifting a load above their head, then clarify this statement by asking whether it is the movement which is painful, the duration of lifting, the manner of lifting or the size of the load which is being lifted that is significant. Night pain, the frequency of waking and the ability to return to sleep are also useful measurement tools. Psychometric disability measures can also be used if they don't result in resentment or irritation from your client.

Further aspects of the subjective examination can be used to assess the past history as it relates to the current problem. Is it the same problem re-aggravated or is it a new problem which is influenced by the old injury? Assess the biomechanical aspects of the original mechanisms of injury as well as those of re-exacerbation, as well as the frequency of exacerbation and make a judgement as to whether the problem is getting worse, better or staying the same. If it is getting worse, then why? Are there components of misuse (reduced co-ordination/stability), disuse (atrophy and reduced capacity of loading), abuse (trauma), or overuse (repetitive loading and microtrauma) which are contributing to the 'cause of the cause' of the problem. A long history of problems may identify fear-avoidance behaviour and generalised 'disuse' and/or of more specific 'disuse' of the multifidus and transverse abdominis muscles. Combine this with 'overuse' of the erector spinae muscles leading to excessive compression of the intervertebral disc and consequent neural irritation of the dorsal root ganglia resulting in ectopic impulse generation and increased muscle tone in the deep hip rotators, hip flexors, hamstring and calf muscles which creates 'misuse' of the lower limbs ('the tail that wags the dog phenomena') generating shearing and rotating forces across the pelvis.

Old injuries may not only reduce the biomechanical integrity of the tissue but it may also increase the neurophysiological sensitivity of the neurones whose nerve fibres innervate the territory of injury. Ascertaining the recuperation from previous injury will provide an insight into the clients 'active' and/or 'passive' coping strategies. People who have had frequent passive treatment inputs and have recovered may find it difficult to embrace a more active treatment approach. Those who haven't recovered may be in a state of 'learned helplessness' who will similarly require convincing to embark on a more active form of recuperation. Importantly, the active treatment approach must embrace the impairment and disability measures of the subjective and physical examinations, thereby allowing the client to measure success leading to the ultimate goal of full self management and/or complete recovery. Therefore, this process requires an element of education whereby the therapist's 'hands-on' treatment becomes 'exercise enabling' and/or 'performance enhancing' for the client.

Figure 4: The application of treatment will vary with the stage, stability, severity and irritability of the condition. The stage describes whether the condition is getting better, worse or staying the same. The stability is considered both mechanically and neurophysiologically. The severity is the impact the injury has on the person's activities of daily living. The irritability defines how easily the symptoms worsen and relates to how quickly they get better. These factors will influence the goals of the client which should direct the aims and objectives of the therapist.

Figure 5: Defining the aspects of the examination heightens the therapists cognitive abilities and hence clinical agility. Reflective skills as treatment is instigated and outcomes are measured enhances the therapist's meta-cognitive skills (thinking about their thinking)

Figure 6: Defining the 'cause of the cause' will get to the root of the problem. By deconstructing the problem clear and precise explanations can be given whereby the aims and objects of treatment commiserate the exercise goals

Cause & effect

Treatment is usually directed at the primary problem for which the client has presented. As the primary problem resolves the cause and affect of the injury must be taken into consideration if an holistic approach is to be considered. Low back pain would address issues of thoracic spine stiffness in rotation, lateral bending and inferior lateral chest expansion as these areas influence the lateral movement of the diaphragm during breathing. In turn this affects the use of the oblique stomach muscles, the transverse abdominus and psoas major. Furthermore, the ganglia of the sympathetic nervous system attach to the anterior aspect of the posterior ribs and their function is influenced by rib movement, which can potentially affect the control of muscle spasms and blood flow to the spine and lower limbs. Finally, deep slow lateral breathing reduces the risk of respiratory alkalosis and hence metabolic acidosis which can affect soft tissue integrity. Looking below the lumbar spine, addressing the pelvis and hips using joint mobilizations, soft tissue massage and muscle energy techniques would affect lumbo-pelvic rhythm. Muscle spasms can be addressed by reducing inflammation and/or relieving mechanical pressure on nerve fibres thereby decreasing ectopic impulse generation. Additionally, dry needling and soft tissue massage of the muscle fibres may also be employed. Exercise regimes to complement the specific impairment outcome measures should be integrated into functional exercises which resemble activities of daily living. Naturally, the clients motivational & emotional state needs to be monitored if a collaborative approach to recovery is to be obtained.

Explanations and References

Manual Therapie in der Behandlung von Schmerzen (Deutsch)

Terapia Manual y dolor (Castellano)

Tratamento do dor e inflamacao com fisioterapia manipulativa (Portuguese)

Manual therapy in the treatment of pain and inflammation (English)

Exercise and the Immune System (English)

Exercise and Sarcopenia (English)

Examples of the assessment process for clinical reasoning

Beispiel von Klinisches Denken

Clinical Reasoning Exercise for low back and lower Limb

Clinical example of treatment for functional instability and radicular LBP

Clinical Reasoning Exercise for Neck-Upper Limb

Apresentacao Clinica e Perguntas

(RACIOCINIO CLINICO)

Presentation at the conference in Rome in October 2005

Publications:

-

Neurophysiological Effects of Traction, Rigaku ryohogaku (2000), 27,4, 128 (Japan)

-

Lumbar Spine Traction: Evaluation of effects and recommended application for treatment (2000), Manual Therapy, 5, 2, 72-81

-

Neurophysiological effects of Manual Therapy (1996), Kinesiologia, (Chile)

-

Neurophysiological considerations of SLR and ULTT (1998), Kinesiologia (Chile)

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

References

Adams, M.A., Dolan, P.& Hutton, W.C. (1986). The stages of disc degeneration as revealed by discogram. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 68B , 36.

Ahmed, M., Bjurholm, A., Kreicbergs, A.& Schultzberg, M. (1993). Sensory and autonomic innervation of the facet joint in the rat lumbar spine. Spine 18 (14), 2121 to 2126.

Alkon, D.L.& Rasmussen, H.A. (1988). A spatial-temporal model of cell activation. Science 239 , 998 to 1005.

Attal, N., Filliatreau, G., Perrot, S., Jazat, F., Di Giamberardino, L.& Guilbaud, G. (1994). Behavioural pain-related disorders and contribution of the saphenous nerve in crush and chronic constriction injury of the rat sciatic nerve. Pain 59 , 301 to 312.

Badalemente, M.A., Dee, R., Ghillani, R., Chien, P-F. & Daniels, K. (1987). Mechanical stimulation of dorsal root ganglia induces increased production of substance P : A mechanism for pain following nerve root compromise? Spine 12 , 552 to 555.

Barasi, S.& Lynn, B. (1986). Effects of sympathetic stimulation on mechanoreceptive and nociceptive afferent units from the rabbit pinna. Brain Research 378 , 21 to 27.

Barker, J.N., Mitra, R.S., Griffiths, C.E., Dixit, V.M.& Nicholoff, B.J. (1991). Keratinocytes as initiators of inflammation. Lancet 337 , 211 to 214.

Barrows, H.S., Tamblyn, R.N., (1980). Problem-based learning: an approach o medical education. Springer, New York.

Blottner, D.& Baumgarten, H.G. (1994). Neurotrophy and regeneration in vivo. Acta Anatomica 150 , 235 to 245.

Bogduk, N. (1993). The anatomy and physiology of nociception. In : Crosbie J.& McConnell, J.(Eds.) (1993). Key Issues in Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy (Ch.3). Oxford : Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.

Butler, D.S., (1991). Mobilisation of the Nervous System . Churchill Livingstone : Melbourne.

Chatani, K., Kawakami, M., Weinstein, J.N., Meller, S.T.& Gebhart, G.F. (1995). Characterization of thermal hyperalgesia, c-fos expression, and alterations in neuropeptides after mechanical irritation of the dorsal root ganglion. Spine 20 (3), 277 to 290.

Coderre, T.J., Basbaum, A.I.& Levine, J.D. (1989). Neural control of vascular permeability : interactions between primary afferents, as cells, and sympathetic efferents. Journal of Neurophysiology 62 , 48 to 58

Coderre, T.J., Chan, A.K., Helms, C.& Levine, J.D. (1991). Increasing sympathetic nerve terminal-dependent plasma extravasation correlates with decreased arthritic joint injury in rats. Neuroscience 40 , 185 to 189.

Coghill, R.C., Mayer, D.J., Price, D.D., (1993). Spinal cord coding of pain : The role of spatial recruitment and discharge frequency in nociception. Pain , 53 , 295 to 309.

Cohen, M.L., (1995). The clinical challenge of secondary hyperalgesia. Moving in on Pain (Abstracts). Adelaide, Australia.

Cohen, M.L., Quintner, J.L., (1993). Fibromyalgia syndrome, a problem of tautology. Lancet , 342 , 906 to 909.

Collingride, G.L.& Singer, W. (1990). Excitatory amino acid receptors and synaptic plasticity. Trends in Pharmacological Science 11 , 290 to 296.

Cornefjord, M., Takahashi, K., Matsui, H., Olmarker, K., Holm, S.& Rydevik, B. (1992). Impairment of nutritional transport at double level cauda equina compression: An experimental study. Neuro Orthopedics 13 , 107 to 112.

Dickenson, A.H.& Sullivan, A.F. (1987). Evidence for a role of the NMDA receptor in the frequency dependent potentiation of deep rat dorsal horn nociceptive neurons following C-fibre stimulation. Neuropharmacology 26 , 1235 to 1238.

Donnerer, J., Amann, R. & Lembeck, F. (1991). Neurogenic and non-neurogenic inflammation in the rat paw following chemical sympathectomy. Neuroscience 45 (3), 761 to 765.

Enwemeka, C.S. & Spielholz, N.I. (1992). Modulation of tendon growth and regeneration by electrical fields and currents. In : Currier, D.P.& Nelson, R.M. (Eds.) (1992). Dynamics of Human Biologic Tissues (ch10). Philadelphia : F.A. Davis Company.

Ferrell, W.R., Wood, L. & Baxendale, R.H. (1988). The effect on acute joint inflammation on flexion reflex excitability in the decerebrate, low-spinal cat. Quarterly Journal Of Experimental Physiology 73 , 95 to 102.

Galea, M.P. & Darien-Smith, I. (1995). Voluntary movement and pain : Focussing on action rather than perception. Moving in on Pain . Adelaide.

Gallin, J.I., Goldstein, I.M. & Snyderman, R. (Eds.) (1992). Inflammation : Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates (2nd ed.). New York : Raven Press.

Gogas, K.R., Presley, R.W., Levine, J.D. & Basbaum, A.,I., (1991). The antinociceptive action of supraspinal opioids results from an increase in descending inhibitory control : Correlation of nociceptive behaviour and C-fos expression. Neuroscience 42 (3), 617 to 628.

Gracely, R.H., Lynch, S.L. & Bennett, G.,J. (1992). Painful neuropathy : Altered central processing, maintained dynamically by peripheral input. Pain 51 , 175 to 194.

Greenbag, P.E., Brown, M.D., Pallares, V.S., Tompkins, J.S. & Mann, N.,H., (1988). Epidural anesthesia for lumbar spine surgery. Journal of Spinal Disorders 1 , 139 to 143.

Gonzales, R., Goldyne, M.E., Taiwo, Y.O. & Levine, J.D. (1989). Production of hyperalgesic prostaglandins by sympathetic postganglionic neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry 53 , 1595 to 1598.

Gonzales, R., Sherbourne, C.D., Goldyne, M.E. & Levine, J.D., (1991). Noradrenaline-induced prostaglandin production by sympathetic postganglionic neurons is mediated by alpha-2-adrenergic receptors. Journal of Neurochemistry 57 , 1145 to 1150.

Green, P.G., Basbaum, A.I., Helms, C. & Levine, J.D. (1991). Purinergic regulation of bradykinin-induced plasma extravasation and adjuvant-induced arthritis in the rat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science , U.S.A. 88 , 4162 to 4165.

Green, P.G., Luo, J., Heller, P.H. & Levine, J.D. (1992). Modulation of bradykinin-induced plasma extravasation in the rat knee joint by sympathetic co-transmitters. Neuroscience 52 , 451 to 458.

Groen, G.J., Balget, B. & Drukker, J. (1988). The innervation of the spinal dura mater: anatomy and clinical considerations. Acta Neurochirurgica 92 , 39 to 46.

Groenblad, M., Weinstein, J.N. & Santavirta, S. (1991). Immunohistochemical observation on spinal tissue innervation. Acta Orthopaedic Scandinavia 62 (6), 614 to 622.

Groenblad, M., Virri, J., Tolonen, J., Seitsalo, S., Kaeaepae, E., Kankare, J., Myllynen, P. & Karaharju, E. (1994). A controlled immunohistochemical study of inflammatory cells in disc herniation tissue. Spine 19 (24), 2744 to 2751.

Handwerker, H.O., Forster, C. & Kirchhoff, C., (1991). Discharge patterns of human C-fibres induced by itching and burning stimuli. Journal of Neurophysiology 66 , 307 to 317.

Harvey, G.K., Toyka, K.V. & Hartung, H.-P. (1994). Effects of mast cell degranulation on blood-nerve barrier permeability and nerve conduction in vivo. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 125 , 102 to 109.

Heller, P.H., Green, P.G., Tanner, K.D., Miao, F.J.-P. & Levine, J.D. (1994). Peripheral neural contributions to inflammation. Progress in Pain Management (1st ed.)(pp31-42). Seattle : IASP Press.

Hodges, P., Richardson, C., (1996). Inefficient muscular stabilisation of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain : A motor control evaluation of transverse abdominis. Spine , 21 , 2640 to 2650.

Hodges, P., Richardson, C., Jull, G., (1996). Evaluation of the relationship between laboratory and clinical tests of transverse abdominis function. Physiotherapy Research International , 1 , 30 to 40.

Hu, S. & Zhu, J. (1989). Sympathetic facilitation of sustained discharges of polymodal nociceptors. Pain 38 , 85 to 90.

Hsieh, J-C., Stahle-Backdahl, M., Hagermark, O., Stone-Elander, S., Rosenquist, G., Ingvar, M., (1995). Traumatic nociceptive pain activates the hypothalamus and the periaqueductal gray: a positron emission tomography study. Pain , 64 , 303 to 314.

Issekutz, T.B. (1992). Inhibition of lymphocyte endothelial adhesion and in vivo lymphocyte migration to cutaneous inflammation by TA-3, a new monoclonal antibody to rat LFA-1. Journal of Immunology 149 , 3392 to 3402.

Jaenig, W. (1985). Organization of the lumbar sympathetic outflow to skeletal muscle and skin of the cat hindlimb and tail. Review of Physiology, Biochemistry, Pharmacology 102 , 119 to 213.

Jaenig, W. & Koltzenberg, M. (1991). Receptive properties of pial afferents. Pain 45 , 77 to 85.

Jones, M., (1995). Clinical Reasoning and Pain. Manual Therapy , 1 , 17 to 24.

Jull, G., Zito, G., Trott, P., Potter, H., Shirley, D., Richardson, C., (1997). Inter-examiner reliability to detect painful upper cervical joint dysfunction. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy , 43 , 2, 125 to 129.

Kalso, E.A., Sullivan, A.F., McQuay, H.J., Dickenson, A.H., Roques, B.P., (1993). Cross-tolerance between Mu Opioid and alpha-2 Adrenergic receptors, but not between Mu and Delta receptors in the spinal cord of the rat. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics , 265 (2), 551 to 558.

Kambin, P., Abda, S. & Kurpici, F. (1980). Intradiskal pressure and volume recording : Evaluation of normal and abnormal intervertebral disks. Clinical Orthopedics 146 , 140.

Kawakami, M., Weinstein, J.N., Chatani, K.-I., Spratt, K.F., Meller, S.T. & Gebhart, G.F. (1994a). Experimental lumbar radiculopathy : Behavioural and histologic changes in a model of radicular pain after spinal nerve root irritation with chromic gut ligatures in the rat. Spine 19 (16), 1795 to 1802.

Kawakami, M., Weinstein, J.N., Spratt, K.F., Chatani, K-I., Traub, R.J., Meller, S.T. & Gebhart, G.F. (1994b). Experimental lumbar radiculopathy : Immunohistochemical and quantitative demonstrations of pain induced by lumbar nerve root irritation of the rat. Spine 19 (16), 1780 to 1794.

Kobayashi, S., Yoshizawa, H., Hachiya, Y., Ukai, T. & Morita, T. (1993). Vasogenic edema induced by compression injury to the spinal nerve root: Distribution of intravenously injected protein tracers and Gadolinium-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Spine 18 (11), 1410 to 1424.

Koltzenburg, M., Kees, S., Budweiser, S., Ochs, G. & Toyka, K.V. (1994). The properties of unmyelinated nociceptive afferents change in a painful chronic constriction neuropathy. In : Gebhart, G.F., Hammond, D.L. & Jensen, T. S. (Eds.) (1994). Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Pain : Progress in Pain and Management (2nd ed.) (Ch.35). Seattle : IASP Press.

Korkala, O., Gronblad, M., Liesi, P. & Karaharju, E. (1985). Immunohistochemical demonstration of nociceptors in the ligamentous structures of the lumbar spine. Spine 10 , 156 to 157.

Kuslich, S.D., Ulstrom, C.L. & Michael, C.J. (1991). The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: A report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operation on the lumbar spine using local anaesthesia. Orthopedic Clinics North America 22 , 181 to 187.

Laird, J.M.A. & Bennett, G.J. (1993). An electrophysiological study of dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord of rats with an experimental peripheral neuropathy. Journal of Neurophysiology 69 , 2072 to 2085.

Laird, J.M.A. & Cervero, F. (1990). Tonic descending infuences on receptive-field properties of nociceptive dorsal horn neurons in sacral spinal cord of rat. Journal of Neurophysiology 63 (5), 1022 to 1032.

LaMotte, R.H., Shane, C.N., Simone, D.A. & Tsai, E.F.P. (1991). Neurogenic hyperalgesia : Psychophysical studies of underlying mechanisms. Journal of Neurophysiology , 66 , 190 to 211.

Levine, J.D., Dardick, S.J., Roizen, M.F., Helms, C. & Basbaum, A.I. (1986). The contribution of sensory afferents and sympathetic efferents to joint injury in experimental arthritis. Journal of Neuroscience 6 , 3923 to 3929.

Levine, J.D., Goldstine, J., Mayes, M., Moskowitz, M.A. & Basbaum, A.I. (1986). The neurotoxic effect of gold sodium thiomalate on the peripheral nerves of the rat. Arthritis and Rheumatism 29 , 897 to 901.

Levine, J.D., Taiwo, Y.O., Collins, S.D. & Tam, J.K. (1986a). Noradrenaline hyperalgesia is mediated through interaction with sympathetic postganglionic neurone terminals rather than activation of primary afferent nociceptors. Nature 323 , 158 to 160.

Lotz, M., Vaughn, J.H. & Carson, D. (1988). Effect of neuropeptides on production of inflammatory cytokines by human monocytes. Science 241 , 1218 to 1221.

Lovick, T.A., (1991). Interactions between descending pathways from the dorsal and ventrolateral periaquaductal gray matter in the rat. In ; Depaulis, A., Bandler, R.,(eds). The Midbrain Periaqueductal Gray Matter . Plenium Press, New York, 101 to 120.

Lima, D., Esteves, F. & Coimbra, A., (1994). C- fos activation by noxious input of spinal neurons projecting to the nucleus of the tractus solitarius in the rat. In : Gebhart, G.F., Hammond, D.L. & Jensen, T.S. (Eds.) (1994). Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Pain : Progress in Pain and Management (2nd ed.) (Ch.30). Seattle : IASP Press.

Liu, J., Roughley, P.J. & Mort, J.S. (1991). Identification of human intervertebral disc stromelysin and its involvement in matrix degeneration. Journal of Orthopedic Research 9 , 568 to 575.

Lundborg, G., (1988). Nerve Injury and Repair . Edinburgh : Churchill Livingstone

MacMillan, J., Schaffer, J.L. & Kambin, P. (1991). Routes and incidence of communication of lumbar discs with surrounding neural structures. Spine 16 , 2, 167 to 171.

Magal, E.L. (1990). Gangliosides prevent ischemia-induced down-regulation of protein kinase C in fetal rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry 55 , 2126 to 2131.

Maitland, G.D. (Ed.) (1986). Vertebral Manipulation (5th ed.). London : Butterworths.

Maitland, G.,D., (Ed) (1991). Peripheral Manipulation . London : Butterworths.

Mao, J., Price, D.D., Coghill, R.C., Mayer, D.J. & Hayes, R.L. (1992). Spatial patterns of spinal cord [14C]-2-deoxyglucose metabolic activity in a rat model of painful peripheral mononeuropathy. Pain 50 , 89 to 100.

Markowitz, S., Saito, K., Buzzi, M.G. & Moskowitz, M.A. (1989). The development of neurogenic plasma extravasation in the rat dura mater does not depend upon the degranulation of mast cells. Brain Research 477 , 157 to 165.

Matsui, H., Olmarker, K., Cornefjord, M., Takahashi, K. & Rydevik, B. (1992). Local electrophysiological stimulation in experimental double level cauda equina compression. Spine , 17 (9), 1075 to 1078.

Maixner, W., Gracely, R.H., Zuniga, J.R., Humphrey, C.B & Bloodworth, G.R. (1990). Cardiovascular and sensory responses to forearm ischemia and dynamic hand exercise. American Journal of Physiology 259 , R1156 to R1163.

McKenzie, R.C. & Sauder, D.N. (1990). The role of keratinocyte cytokines in inflammation and immunity. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 95 , S105 to 107.

Morton, C.R., Siegel, J., Xiao, H.-M., Zimmermann, M., (1997). Modulation of cutaneous nociceptor activity by electrical stimulation in the brain stem does not inhibit the nociceptive excitation of dorsal horn neurons. Pain , 71 , 65 to 70.

Morgan, M.M., Sohn, J.-H., Lohof, A.M. Ben-Eliyahu, S. & Liebeskind, J.C. (1989). Characterization of stimulation-produced analgesia from the nucleus tractus solitarius in the rat. Brain Research 486 , 175 to 180.

Nakagawa, I., Omote, K., Kitahata, L.M., Collins, J.G. & Murata, K. (1990). Serotonergic mediation of spinal analgesia and its interaction with noradrenergic systems. Anesthesiology 73 , 474 to 478.

Nishizuka, Y. (1989). The family of protein kinase C for signal transduction. JAMA 262 , 1826 to 1833.

Ochoa, J.L. & Yarnitsky, D. (1993). Mechanical hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain patients : Dynamic and static subtypes. Annals of Neurology 33 , 465 to 472.

Olmarker, K., Rydevik, B., Holm, S. & Bagge, U. (1989). Effects of experimental, graded compression on blood flow in spinal nerve roots. A vital microscope study on the porcine cauda equina. Journal of Orthopedic Research 7 , 817 to 823.

Olmarker, K., Rydevik, B. & Nordborg, C. (1993). Autologous Nucleus Pulposus induces neurophysiological and histological changes in porcine cauda equina nerve roots. Spine 18 (11), 1425 to 1432.

Petersen, N.,P., Vicenzino, B., Wright, A., (1993). The effects of a cervical mobilisation technique on sympathetic outflow to the upper limb in normal subjects. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice , 9 , 149 to 156.

O?Sullivan, P., Twomey, L., Allison, G., Sinclair, J., Miller, K., Knox, J., (1997). Altered patterns of abdominal muscle activation in patients with chronic low back pain. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy , 43 , 91 to 98.

Post, C., Minor, B.G., Davies, M. & Archer, T. (1986). Analgesia induced by 5-hydroxytryptamine-depletion in rats. Brain Research 363 , 18 to 27.

Price, D.D., Long, S. & Huitt, C. (1992). Sensory testing of pathophysiological mechanisms of pain in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Pain 49 , 163 to 173.

Price, D.D., Mao, J. & Mayer, D.J. (1994). Central neural mechanisms of normal and abnormal pain states. In Fields, H.L. & Liebeskind, J.C. (Eds.)(1994). Progress in Pain Research and Management (1st ed.)(pp61-84). Seattle : IASP Press.

Proudfit, H.K. (1992). The behavioural pharmacology of the noradrenergic descending system. In : Besson, J.M. & Guilbaud, G. (Eds.)(1992). Towards the use of Noradrenergic Agonists for the Treatment of Pain (1st ed.). Amsterdam : Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

Quintner, J.L., Cohen, M.L., (1994). Referred pain of peripheral nerve origin : an alternative to the 'myofascial pain construct'. Clinical Journal of Pain , 10 , 243 to 251.

Raja, S.N., Meyer, R.A. & Campbell, J.N. (1988). Peripheral mechanisms of somatic pain. Anesthesiology 68 , 571 to 590.

Rees, H., Sluka, K.A., Westlund, K.N. & Willis, W.D. (1994). Do dorsal root reflexes augment peripheral inflammation ? NeuroReport 5 , 821 to 824.

Ren, K., Randich, A. & Gebhart, G.F. (1990). Modulation of spinal nociceptive transmission from nuclei tractus solitarii : A relay for effects of vagal afferent stimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology 63 (5), 971 to 986.

Roberts, W.J. & Elardo, S.M. (1985). Sympathetic activation of unmyelinated mechanoceptors in cat skin. Brain Research 339 , 123 to 125.

Rothwell, N.J. & Hopkins, S.J. (1995). Cytokines and the nervous system II : actions and mechanisms of action. Trends in Neuroscience 18 , 130 to 136.

Rydevik, B.L., Brown, M.D. & Lundborg, G. (1984). Pathoanatomy and pathophysiology of nerve root compression. Spine 9 , 7 to 15.

Rydevik, B.L., Myers, R.R. & Powell, H.C. (1989). Pressure increase in the dorsal root ganglion following mechanical compression: Closed compartment syndrome in nerve roots. Spine 14 (6), 574 to 576.

Sandkuehler, J., Eblien-Zajjur, A., Fu, Q.-G. & Forster, C. (1995). Differential effects of spinilization on discharge patterns and discharge rates of simultaneously recorded nociceptive and non-nociceptive spinal dorsal horn neurons. Pain 60 , 55-65.

Sanjue, H. & Jun, Z. (1989). Sympathetic facilitation of sustained discharges of polymodal nociceptors. Pain 38 , 85-90.

Schmidt, R.F. (1990). Experimental arthritis. Pain (supp) 5 , S215.

Schmidt, R.F., Schaible, H.-G., Messlinger, K., Heppelmann, B., Hanesch, U. & Pawlak, M. (1994). Silent and active nociceptors : Structure, functions, and clinical implications. In : Gebhart, G.F., Hammond, D.L. & Jensen, T. S. (Eds.) (1994). Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Pain : Progress in Pain and Management (Ch.16) (2nd ed.). Seattle : IASP Press.

Shindo, K., Tsunoda, S-T.& Shiozawa, Z. (1994). Muscle spasm induced sympathetic reflex bursts on microneurography in a case with pontine demyelination. Clinical Autonomic Research 4 , 299 to 302.

Schomburg, E.,D. & Steffens, H. (1992). On the spinal motor function of nociceptive afferents and enkephalins. In : Jami, L., Pierrot-Deseilligny, E. & Zytnicki, D. (Eds.)(1992). Muscle Afferents and Spinal Control of Movement (pp.395 to 400)(1st ed.). Oxford : Pergamon Press.

Suval, W.D., Duran, W.N., Boric, M.P., Hobson, R.W., Berendsen, P.B. & Ritter, A.B. (1987). Microvascular transport and endothelial cell alterations preceding skeletal muscle damage in ischemia and reperfusion injury. The American Journal of Surgery 154 , 211 to 218.

Taiwo, Y.O. & Levine, J.D. (1989). Prostaglandin effects after elimination of indirect hyperalgesic mechanisms in the skin of the rat. Brain Research 492 , 397 to 399.

Takahashi, K., Olmarker, K., Holm, S., Porter, R.W. & Rydevik, B. (1993). Double level cauda equina compression. An experimental study with continuous monitoring of intraneural blood flow in the porcine cauda equina. Journal of Orthopedic Research 11 (1), 104 to 109.

Thompson, S.W.N. & Woolf, C.J. (1991). Primary afferent-evoked prolonged potentials in the spinal cord and their central summation : Role of the NMDA receptor. In : Bond, M.R., Charlton, J.E. & Woolf, C.J. (Eds). Proceedings of the VIth World Congress on Pain (pp291 to 298). Amsterdam : Elsevier

Tillman, L.J. & Cummings, G.S. (1992). Biologic mechanisms of connective tissue mutability. In : Currier, D.P. & Nelson, R.M. (Eds.) (1992). Dynamics of Human Biologic Tissues (pp1-44). Philadelphia : F.A. Davis Company.

Torebjoerk, E. (1994). Nociceptor dynamics in humans. In : Gebhart, G.F., Hammond, D.L. & Jensen, T. S. (Eds.) (1994). Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Pain : Progress in Pain and Management (Ch.19) (2nd ed.). Seattle : IASP Press.

Troisier, O. & Cypel, D. (1986). Discography: An element of decision. Clinical Orthopedics 206 , 70.

Urban, L. & Randic, M. (1984). Slow excitatory transmission in rat dorsal horn : Possible mediation by peptides. Brain Research 290 , 336 to 341.

Vaccarino, F., Guidotti, A. & Costa, E. (1987). Ganglioside inhibition of glutamate-mediated protein kinase C translocation in primary cultures of cerebellar neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science , U.S.A. 34 , 8707.

Wall, P.D. (1995). Treatment of pain. Moving in on Pain . Adelaide.

Wall, P.D. & Devor, M. (1983). Sensory afferent impulse originate from dorsal root ganglia as well as from the periphery in normal and nerve injured rats. Pain 17 , 321 to 339.

Wall, P.D. & Melzak, R. (1989) (Eds.). Textbook of Pain , (2nd. ed.). Edinburgh : Churchill Livingstone.

Weinstein, J.N., Claverie, W. & Gibson, S. (1988). The pain of discography. Spine 13 (12), 1344 to 1348.

Williams, T.J. & Hellewell, P.G. (1992). Endothelial cell biology. Adhesions molecules involved in the microvascular inflammatory response. American Review of Respiratory Disease 146 , S45 to 50.

Wiltse, L.L., Fonseca, A.S., Amster, J., Dimartino, P. & Ravessoud, F.A. (1993). Relationship of the dura, Hofmann's ligaments, Batson's plexus, and a fibrovascular membrane lying on the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies and attaching to the deep layer of the posterior longitudinal ligament: An anatomical, radiological, and clinical study. Spine 18 (8), 1030 to 1043.

Woolf, C.J. (1983). Evidence for a central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Nature 306 , 686 to 688.

Woolf, C.J. (1984). Long-term alterations in the excitability of the flexion reflex produced by peripheral tissue injury in the chronic decerebrate rat. Pain 18 , 325 to 343.

Woolf, C.J. & McMahon, S.B. (1985). Injury-induced plasticity of the fexor reflex in chronic decerebrate rats. Neuroscience 16 , 395 to 404.

Woolf, C.J., Shortland, P. & Sivilotti, L.G. (1994). Sensitization of high mechanothreshold superficial dorsal horn and flexor motor neurones following chemosensitive primary afferent activation. Pain 58 , 141 to 155.

Woolf, C.J. & Swett, J.E. (1984). The cutaneous contribution to the hamstring flexor reflex in the rat : an electrophysiological and anatomical study. Brain Research 303 , 299 to 312.

Woolf, C.J. & Wall, P.D. (1986). Relative effectivenss of C primary afferent fibres in evoking a prolonged facilitation of the flexor reflex in the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience 6 , 1433 to 1442.

Wright, A., Vicenzino, B., (1995). Cervical mobilisation techniques, sympathetic nervous system effects and their relationship to analgesia. In : Schacklock, M.,O., (ed.). (1995). Moving in on Pain , Butterworth-Heineman, 164 to 173.

Xavier, A.V., Farrell, C.E., McDanal, J. & Kissin, I. (1990). Does antidromic activation of nociceptors play a role in sciatic radicular pain? Pain 40 , 77 to79.

Zochodne, D.W. (1993). Epineural peptides : A role in neuropathic pain? Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 20 (1), 69 to 72.